History

Visiting Parke’s Castle feels like diving into the political scene of the 16th and 17th centuries in Ireland and hence into the history of a land contended between Irish clans and English planters. Thankfully, the Office of Public Works (OPW) [1], who is taking care of this beautiful site, introduced us to an intricate past and guided us through the corridors, rooms and yards of Parke’s castle, showing all its secrets… At least those that the castle has disclosed up until now 😉

Unless otherwise specified, the information reported here is what we learned during our guided tour and what we found in a precious, well detailed brochure, also by the OPW [1], that we collected at the entrance of the site.

No more time waste, let’s talk about the castle!

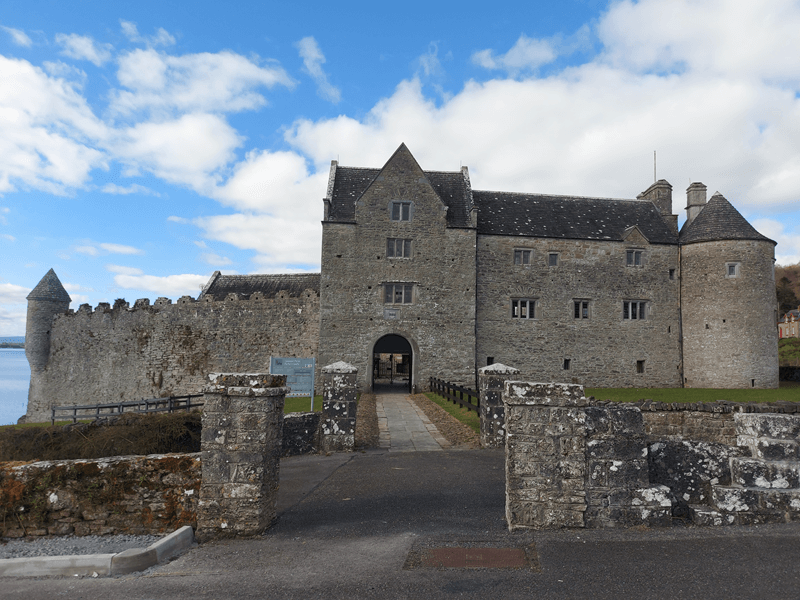

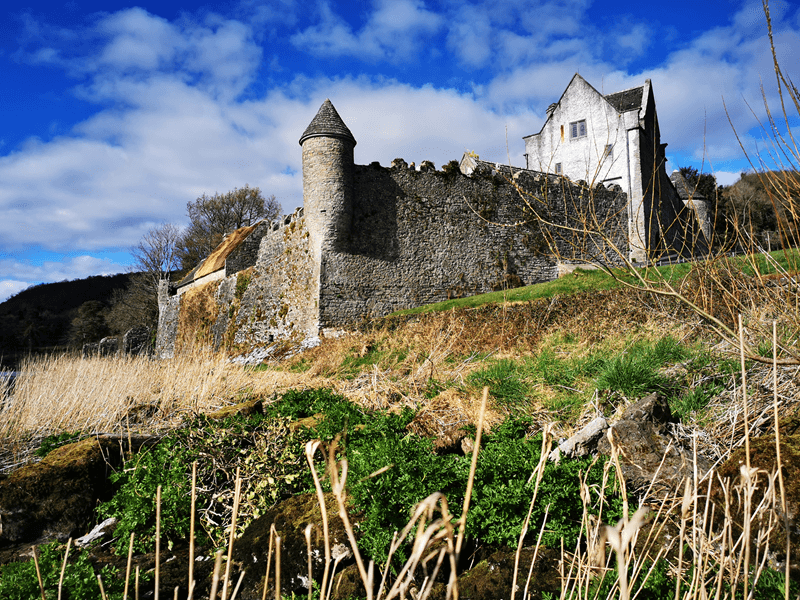

Parke’s Castle is a fortified Manor House of the 17th century Plantation period, located beside the Leitrim shore of Lough Gill, in a unique landscape celebrated in his verses by the Irish poet William Butler Yeats [2].

Both Irish and English contributed to Parke’s Castle, in two different periods. Indeed, already during the 16th century, the powerful local gaelic family of the O’Rourkes had erected here a tower house. Some of the main elements which are still visible (i.e., the gatehouse, the perimetral walls around the courtyard and the north-eastern tower) date back to this phase. The Manor House, instead, was later built by Robert Parke in the 1620’s [1, 3].

It is interesting to understand how the site belonging to the O’Rourkes ended up in English hands, as it probably gives an idea of the political framework in Ireland during those years. In more detail, in 1588, Brian na Murtha O’Rourke, the last proper chieftain of Breifne and devout Roman catholic [4], sheltered Francisco de Cuellar, a shipwrecked Spanish Armada Officer, provoking the angry reaction of Queen Elizabeth I who indicted Brian for high treason. This was the time of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) and the Spanish Armada landing in Ireland was perceived as a threat to England's security [3]. In more detail, after the great sea battle off the Cliffs of Dover, the Spanish Armada was defeated and Brian O'Rourke had already given refuge to at least other eighty of the Spanish sailors and soldiers who were shipwrecked at Streedagh, before hosting Francisco de Cuellar [4].

Brian managed to escape, travelling first to Doe Castle in County Donegal, where he remained for a year, and then he moved to the Kingdom of Scotland, where he tried to seek help from King James VI, the son of Mary Queen of Scots and a cousin of Queen Elizabeth, and to raise an army [3, 4]. Unfortunately, Brian was then arrested on the orders of King James VI, under pressure from his relative, Elizabeth I, extradited to London, thrown into the Tower of London and then hanged at Tyburn in 1591 [1, 3]. Interestingly, this could have been the first known case of extradition for crimes committed in another country [4].

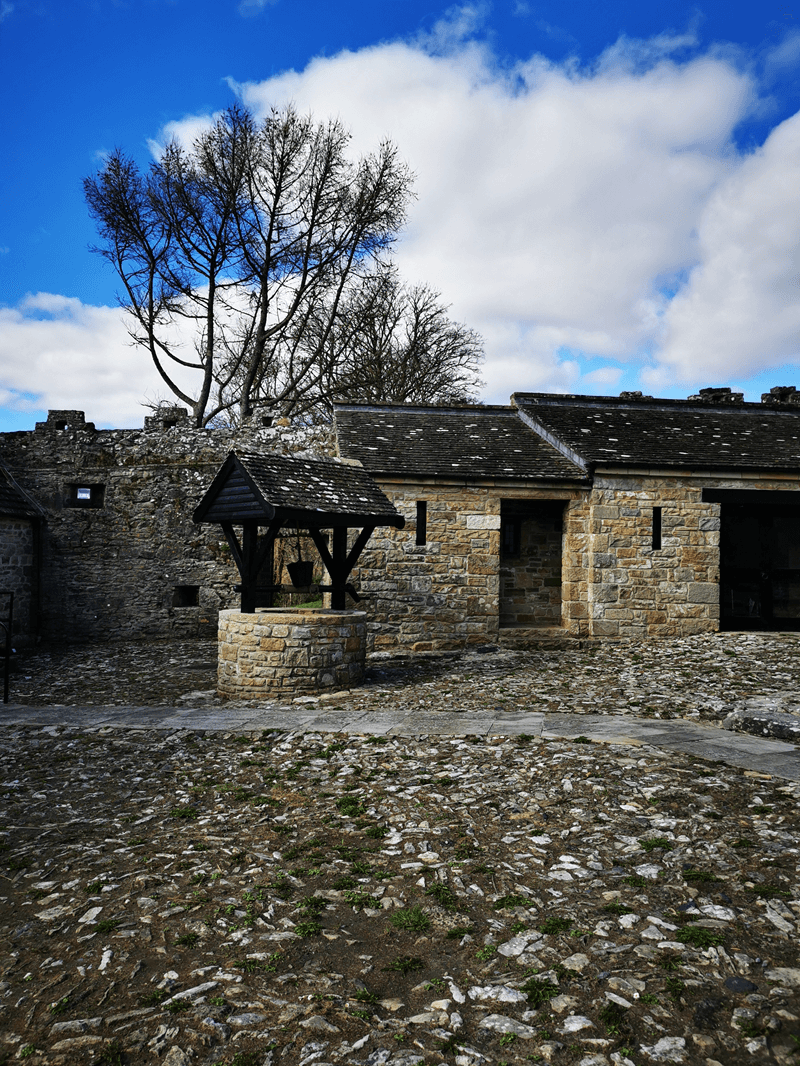

In his diary, Captain de Cuellar wrote about him that ‘although the chief is a savage, he is a good Christian and an enemy of the heretics and is always at war with them’. Also, the original tower house was teared down by the same O’Rourke to prevent it from falling into English hands [3, 4]. The foundations of the O'Rourke tower house were discovered under the cobblestones in the courtyard, during the excavations carried out in the 1970’s [3].

Brian's son, Brian Óg O'Rourke, eventually inherited his father’s title and, keen to avenge his father's death and assert his rights as a Gaelic ruler, joined with Red Hugh O'Donnell and the Earl of Tyrone, Hugh O'Neill, when the Nine Years War began in 1593 [3, 4]. Brian Og was the last of the Gaelic chieftains to surrender at the end of the war [4].

King James VI of Scotland succeeded Queen Elizabeth upon her death in 1603, becoming James I of England, and ruled until 1625 [4]. James sanctioned that O’Rourke’s lands were eventually confiscated and redistributed in the plantation of Country Leitrim [4]. In the 1620’s, it is recorded that Captain Robert Parke of ‘Newtowne’ (‘Baile Nua’, as it was known during the O’Rourkes time, from which the name ‘Newtown Castle’) had already acquired about 1000 acres in mortgage from Con O’Rourke, ‘An Irish papist’. The first Parke to settle in Ireland was Robert’s father, Roger of Dunally, Co. Sligo, who arrived in Ireland from Kent at the beginning of the 17th century.

Robert Parke demolished what was remaining of the O’Rourke’s tower house and used the stones to build first a four-storey gate tower, possibly with a timber house attached, followed a few years later by the fortified manor house now known as Parke’s Castle [4]. He added two circular towers, the larger used to house soldiers and the smaller for pigeons, and a pair of smaller turrets towards the lake [4]. He also added a water gate, to permit entry and exit by water in case of emergency [4].

Robert Parke employed many Irish among his staff and kept a native harper, Dermond O'Farry in his castle, and ultimately seems to have been a well-liked landlord [4]. He was elected Member of Parliament for Roscommon in 1641 [4].

When the 1641 Rebellion broke out, at least 150 refugees, mainly English planters and tradesmen from around North Leitrim, found shelter in Newtown castle (1642), while the O'Rourkes and other natives were trying to gain their lands back [4]. Robert Parke attempted to stay neutral, refusing to take any action against the native population and hence avoiding any retaliation from the Irish rebels [3, 4]. With that, in 1642, Parke was imprisoned by Sir Frederick Hamilton on suspicion of disloyalty to Cromwell’s Commonwealth and held prisoner for eighteen months [4].

After that, the castle was seized by the O’Haras, a Gaelic family based in Sligo, who held it until 1652 when it was surrendered to Sir Charles Coote on behalf of the Parliamentarians.

When in 1660 the monarchy was restored with Charles II after the parliamentarian experience, thanks to his royalist sympathies, Captain Parke gained back the control on the castle and he became Member of Parliament for Leitrim in 1661. He married Anne Povey of County Roscommon (perhaps Anne was his second wife [4]) and they had three children, Robert and Mary, who both died in 1677 drowned on the lake, and Anne, who married Sir Francis Gore of Ardtarmon, Co. Sligo. Their son, Robert Gore, might have been the last resident of the Manor House. Obviously, when we asked AI to tell us more about Parke’s castle, we learned that the spirit of the daughter of Captain Robert Parke tragically dead in the lake is still haunting the castle, as some visitors might have reported. Somehow, this adds to the castle’s eerie allure.

Moreover the small village at Newtown continued to exist after the events related to the rebellion of 1641, with 59 residents listed in a survey from 1659, and twenty houses mentioned in 1714 [4].

It is not known when the Gore family left the castle anyway a drawing by Sir Thomas Cocking dating 1791 shows it as being in a ruinous state and it probably remained uninhabitated for about two centuries [4]. However, recent archaeological excavations brought to light objects and material from the 18th and 19th centuries, indicating reuse of the site (the bawn, for example, was still used as a farmyard and stables by local residents) [5].

The site was eventually purchased by the Irish Free State in 1935 [3] and, in the late 20th century, it was restored, using traditional Irish oak and craftsmanship.

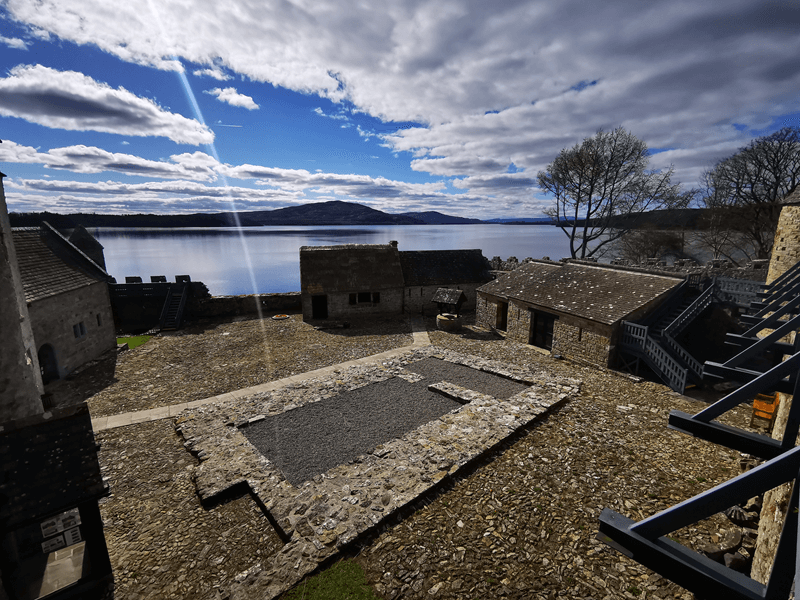

What we can see today is a typical example of a plantation settlement, combining a castle and a walled enclosure. The manor house and attached gatehouse are located on the eastern side of the pentagonal bawn. The other three sides are protected by parapet walls pierced with musket loops and by circular towers at the corners of the bawn, one of which was incorporated into the frontal domestic structures. The entrance to the castle is located in a gabled gatehouse. The Manor house has three storeys with internal stair well with a large staircase and beyond the stairs there were the kitchen and stores. The manor house is connected to the round north-eastern tower which would have acted as a lookout and a stair present here would have allowed both family and soldiers to move speedily from one floor to another in case of attack. The sleeping rooms are located upwards and can be reached through restored stairs at the southern end of the hall.

What we can see today is a typical example of a plantation settlement, combining a castle and a walled enclosure. The manor house and attached gatehouse are located on the eastern side of the pentagonal bawn. The other three sides are protected by parapet walls pierced with musket loops and by circular towers at the corners of the bawn, one of which was incorporated into the frontal domestic structures. The entrance to the castle is located in a gabled gatehouse. The Manor house has three storeys with internal stair well with a large staircase and beyond the stairs there were the kitchen and stores. The manor house is connected to the round north-eastern tower which would have acted as a lookout and a stair present here would have allowed both family and soldiers to move speedily from one floor to another in case of attack. The sleeping rooms are located upwards and can be reached through restored stairs at the southern end of the hall.

An additional residential accomodation in the gatehouse may have been used to host a garrison of soldiers, who would have also occupied the site. We asked our OPW guide how many soldiers were meant to stay in that circular room. The answer was surprisingly more than 30, continuously sharing a small room. However, we were explained that back then having a roof and sufficient food was a privilege, if compared with the majority of people, who did not even have an accomodation.

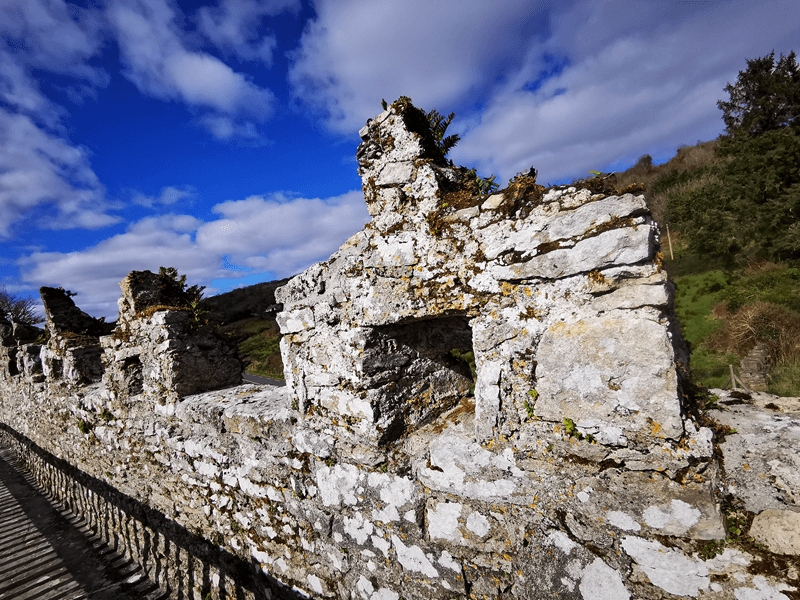

From here, the bawn wall walkway can be accessed, with its crenellated battlements and musket-holes and to the turret, connecting the frontal building to the opposite flanker tower, probably used as a pigeon house.

Thanks to the archeaological excavations carried out in the 1980’s, other 17th century structures built by Parke have been unvealed inside the bawn, such as a blacksmith’s forge, a well and a water-gate to the lake to be used in case of emergence to leave the castle.

An example of a sweathouse is also present just out of the castle’s walls. It is a stone-built sauna-type facility on the lakeshore, associated with this region. Our OPW guide explained that most of the sweathouse that survived are located in country Leitrim and they were probably commonly used by the local Irish families. Difficult to imagine the old Captain Parke in there and, after the sauna, jumping straight into the lake. I am sure though that the reader would not need a huge effort of imagination to see Brian O’Rourke doing that. With the plantation, these structures become less common, also because science saw in them an effective way to spread diseases and pandemics. However, the fact that Robert Parke did not demolish it and tolerated its use confirms his intention of gaining the favour of the local Irish people after the O’Rourkes were ousted.

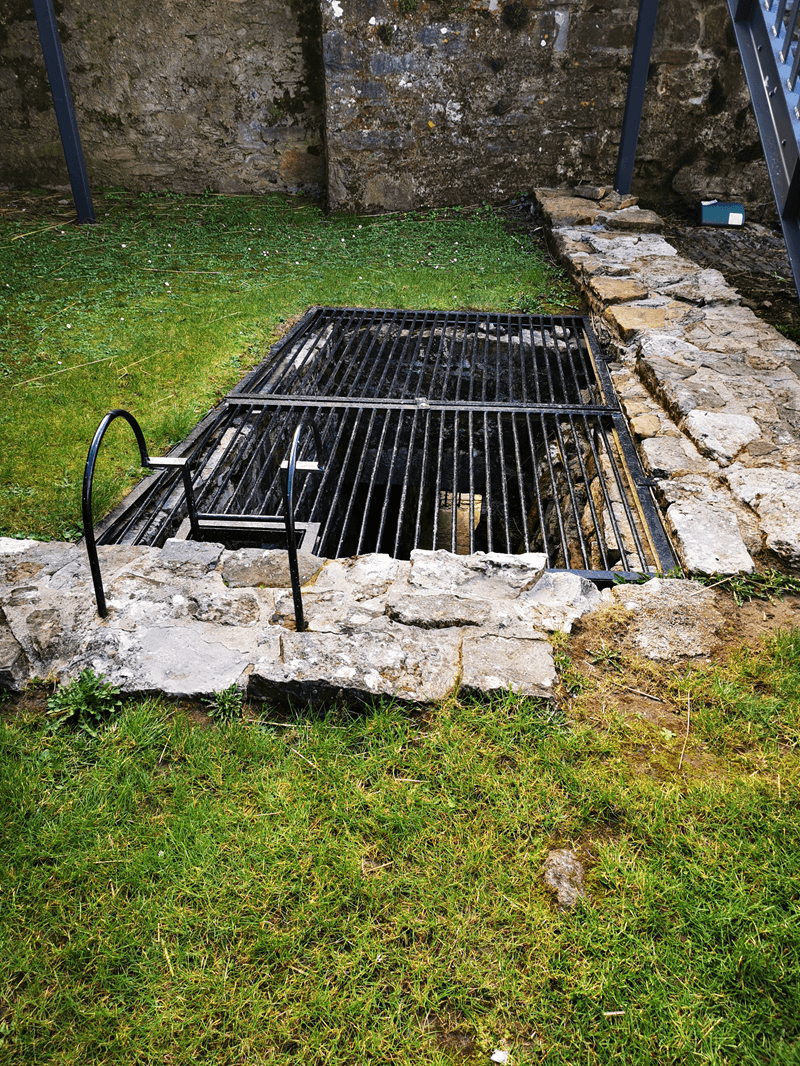

Finally, the most interesting element emerged during these archaeological digs was the discovery beneath Parke’s cobbled courtyard of the foundations of an older rectangular tower house, dating back to the 16th century, which most likely was the residence of Brian O’Rourke.

For a more detailed description of the castle, please refer to [1] and [4].

We hope you enjoyed this virtual tour at Parke’s Castle.

References

- [1] Patrick Comerford, Shanid Castle, a hill-top ruin near Shanagolden, was a Desmond stronghold

- [2] Anglo-Norman Castles Paul Martin Remfry, Shanid

- [3] Shanagolden National School, A History of Shanagolden

- [4] Duchas.ie, Shanid Castle - Another Version

- [5] Duchas.ie, Shanid Castle

Other useful links

- Shanagolden.eu, Shanid Castle

- The Shanid Historical Society Shanagolden, Shanid Castle

- Wikipedia, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke

- Wikipedia, Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland

- Wikipedia, Maurice FitzGerald, Lord of Llanstephan

- Wikipedia, Thomas FitzMaurice FitzGerald

- Wikipedia, Knight of Glin

- Wikipedia, Desmond Rebellions

- Wikipedia, Irish Rebellion of 1641