History

Introduction

The beauty of visiting a historical building is in the tales it unfolds. Matisse once said “there are always flowers for those who want to see them” and this is true also for those who, roaming in the Irish countryside, stumble on a castle and are able to unleash their imagination and use it to get lost in its past.

Among all the castles we visited, one particularly fascinating is Killua. Some of the most significant events that shaped the evolution of Ireland are crystallized in the walls of this house. Differently from other historical buildings, Killua is still alive, silently witnessing the colours of the seasons changing in County Westmeath and, after going through centuries of troubles, it is having now its finest hour.

Gathering reliable information about the background of Killua would have been hard if we did not have the book by Andrew Hughes [1], result of a meticulous research on the events that signed changing fortunes of this residence, the surrounding estate and the people whose lives orbited around it. We strongly encourage anyone who is interested in Irish history to read this book, before visiting the castle, as it will give the visitor the necessary background to fully enjoy the tour. Additionally, the reader can check out the website dedicated to the castle [2] and book a guided tour at Killua.

Unless otherwise specified, [1] and [2] will be the main sources of information we will be referring to. A useful synopsis of the content of the book, with a brief introduction to its structure, can be also found in [3].

Before the Castle

The reader might already know that the story of Killua is strongly connected to the rise and fall of the wealthy Anglo-Irish Chapman family. In particular, it was Sir Thomas Chapman who built Killua castle (or St Lucy, as it was originally named) towards the end of the 18th century.

However, a lot had happened before that, so let’s take a step back to the second half of the 16th century, when John Chapman and his brother William Chapman moved from the English county of Leicestershire to Ireland, under the powerful aegis of Sir Walter Raleigh, possibly their cousin. It was the time of the second Desmond Rebellion (1579-1583), between the Anglo-Norman Fitzgeralds, held by the Earl of Desmond, and the other Anglo-Norman dynasty of the Butlers, supported by the English crown. In 1583, the Earl of Desmond was captured and beheaded, marking the end of the Desmond Rebellions and the beginning of the Plantation of Munster. The Fitzgerald’s estate in Munster was first forfeited to the Crown and then distributed among English settlers, who were known as “undertakers”. Probably as a reward for his service and thanks to the influence of the powerful Walter Raleigh, John Chapman was granted lands in the Dingle Peninsula (in county Kerry) that included the Smerwick bay, where a cruel battle had been fought in 1580, engraved in the Irish collective memory as “the massacre of Smerwick”. With that, it is reasonable to suspect that John Chapman took part in that battle.

Let’s take a small leap forward, to the beginning of the 17th century. Fallen from the favour of King James I and accused of conspiracy (“Main Plot”), Raleigh was executed in 1618. Meanwhile, John Chapman had accrued debts and, in 1606, sold his lands in Kerry to Richard Boyle, the 1st Earl of Cork.

John Chapman passed some years later. His brother William died around 1625 and his son, Benjamin Chapman, decided to pursue a military career, serving in the regiment under Murrough O’Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin.

It was a period of political changes in Ireland, culminating in the Irish Confederate Wars (1641-1653). The Irish Catholic Confederation was established in 1642, intending to end the anti-Catholic discrimination and to restore an Irish self-government. Overseas, the political situation in England was also unstable. In 1642, due to disagreements on how to handle the Irish crisis, the English Civil War broke out, with Parliamentarians defeating Royalists and King Charles being executed in 1649. A large English Parliamentarian army, led by Oliver Cromwell, was sent to Ireland and crushed the rebellion. Catholicism was forbidden and Ireland was annexed to the English Commonwealth, a republic which lasted until 1660, when Charles II, the eldest son of Charles I, was nominated King of England, Scotland and Ireland.

With this brief introduction, we only intend to give a glimpse of the turbulent time in which our protagonist, Benjamin Chapman, decided to enroll in the royalist cavalry. Probably, at some point, Benjamin moved to the Parliamentarians side and hence, when the English Parliament started distributing the lands confiscated from the Irish Confederates to the soldiers who supported the campaign, Benjamin was granted a significant estate at Killua, in the village of Clonmellon, located in the barony of Delvin, in County Westmeath. This happened by 1659. The grant of Killua was forfeited by the local Richard Nugent, 2nd Earl of Westmeath and 16th Baron Delvin.

When Charles II was restored, some lands were returned to their former Catholic landowners. This was not the case of Killua, perhaps because Benjamin Chapman had served the royalist cause. In [4] it is suggested that Benjamin Chapman might have been spared from Parliament’s fall, maybe because of his purely military rank.

William Chapman succeeded his father Benjamin after his death, circa 1658. He married Ismay Nugent of Clonlost, related to the Earls of Westmeath, who occupied the estate before it was granted to Benjamin Chapman. Probably this marriage also aimed to legitimate the Chapman’s control over the forfeited lands. William and Ismay had 2 sons, the firstborn named Benjamin, and two daughters.

Chapman Baronetcy and construction of the Castle

Benjamin married twice and from his second marriage he had two sons, Benjamin (future 1st Baronet) and Thomas (2nd Baronet).

Junior Benjamin, born around 1745, pursued a career in politics and became member of Parliament, expanding the Chapman’s influence in the Irish politics. Furthermore, in 1776, a convenient marriage between Benjamin and Anne, daughter of John Lowther of Staffordstown, enriched the Chapman’s finances, providing the resources for the construction of the Georgian mansion, initially known as St Lucy (later Killua Castle).

The political career of Benjamin Chapman came to an end at the general elections in 1783. In these years, Ireland experienced a period of increased independence with the Grattan’s Parliament, often contrasted by Benjamin. As a result, after the Parliament of Ireland was abolished in 1798 in consequence of the Irish Rebellion by the United Irishmen, Benjamin was not reelected but he was created 1st Baronet of St Lucy by the King.

Once retired from politics, Sir Benjamin Chapman spent the rest of his life in the creation of a fine house, that could suit the prestige of his title, before dying in 1810, succeeded by his brother Thomas as the 2nd Baronet.

The house built by Sir Benjamin was a 3-storey neoclassical mansion, whose initial layout consisted of a hall, dining room, an oval drawing room and breakfast room, with front and back stairs, perhaps designed by the famous English architect Thomas Cooley.

Differently from his brother, Sir Thomas had a brilliant military career, reaching the rank of lieutenant-colonel in 1796. Despite his valuable contribution to the British cause, he underwent a court martial trial and found guilty but King George III decided to simply let him retire from the service. In this way, since his return to Killua in 1799, Sir Thomas could totally focus on the management of his estate and the renovation of the family residence.

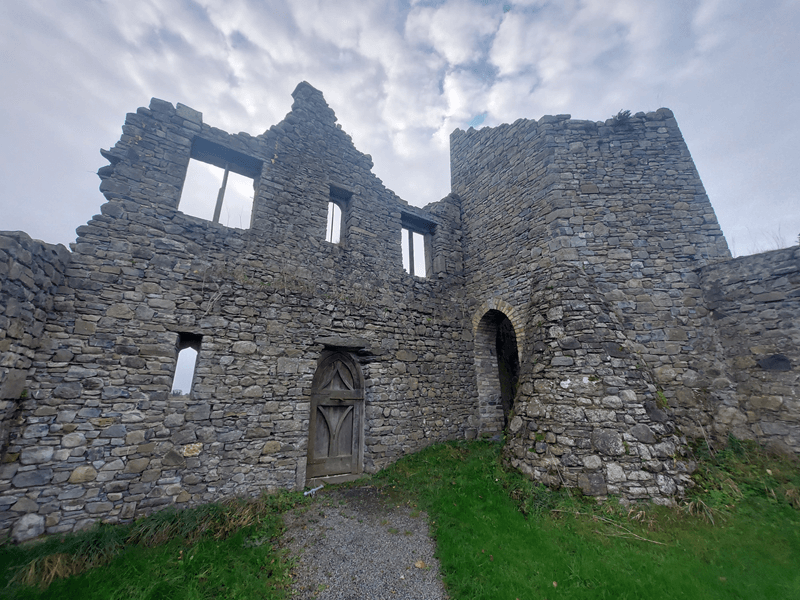

With the help of the architect James Shiel, the Georgian manor of St Lucy’s was turned into Killua Castle by Sir Thomas Chapman, the 2nd Baronet. He replaced the initial staircase with a neo-gothic staircase tower. Moreover, as explained in [4], Sir Thomas’s tastes were strongly influenced by the gothic style, to the point that he added the round tower, the library tower, castellations, a secret passage out into the gardens and other gothic elements. Close to the castle, a folly was added by Sir Thomas around 1800, to resemble the remains of a medieval building.

With the help of the architect James Shiel, the Georgian manor of St Lucy’s was turned into Killua Castle by Sir Thomas Chapman, the 2nd Baronet. He replaced the initial staircase with a neo-gothic staircase tower. Moreover, as explained in [4], Sir Thomas’s tastes were strongly influenced by the gothic style, to the point that he added the round tower, the library tower, castellations, a secret passage out into the gardens and other gothic elements. Close to the castle, a folly was added by Sir Thomas around 1800, to resemble the remains of a medieval building.

The Raleigh Obelisk, which can be found close to the Castle, was also erected by Sir Thomas in 1834. A legend claims that the monument celebrates the arrival of the potato in Ireland by the hand of Raleigh, who planted it first exactly where the obelisk stands. With a smile on his face, the present landlord of Killua explained us that this was just a made up story.

Sir Benjamin, the 1st Baronet had no children, and Sir Thomas, the 2nd Baronet, was widowed and without sons (his only son possibly died in 1798). In 1808, Sir Thomas married Margaret Anne, who gave birth to three sons, Montagu Lowther, Benjamin James (who later became 3rd and 4th Baronets respectively) and William.

We are at the beginning of the 19th century, when the influence of Daniel O’Connell became pervasive among Irish people. In this situation, Sir Thomas encouraged his son Montagu to run for the elections in 1830, when King George IV died. Montagu managed to get elected for Westmeath and to start with that a long political career, supporting the Liberal Party.

When his father, Sir Thomas, passed away, Montagu succeeded him to the baronetcy and the estate of Killua in 1837. In 1841, health related issues forced Sir Montagu to abandon his charge of Member of Parliament for Westmeath in favour of his brother Benjamin James.

After that, Montagu turned his attention towards the expansion of the family properties in Australia. During the Great Famine (1845-1852), Sir Montagu helped to move emigrants to his estate near Port Adelaide. The last records about Sir Montagu date 1852, when the vessel named Favourite where he was aboard for a sea voyage from Melbourne to Sydney tragically disappeared. More information about the life of Sir Montagu are available in [5].

His Irish and Australian estates were inherited by his brother Sir Benjamin James Chapman, 4th Baronet, who was responsible for other important additions to Killua Castle, as the Victorian wing and the crenelated tower on the south-east corner.

Chapman decline

In 1849 Sir Benjamin James married his cousin, Maria Sarah Fetherstonehaugh. They had a daughter, Dora Marguerite, and two sons, Montagu Richard and Benjamin Rupert, who would later become the 5th and 6th Baronets respectively.

Before digging into the lives of the new Chapman generation, we need to zoom out once again and give an overview of the general situation in Ireland. The Irish National Land League (in Irish Conradh na Talún), founded in the late 19th century, supporting tenant farmers against landowners, started the “Land War” (1879-1882). When the government approved the Land Act (1881), the Irish Land Commission was created, intending to purchase estates from landlords and to assign them to small farmers.

Sir Benjamin James died in 1888. The heir, Sir Montagu Richard Chapman, 5th Baronet, married in 1894 his cousin Caroline Margaret Chapman.

Between 1906 and 1909, the Land War evolved into the Ranch War, with small tenant farmers requesting the sale of untenanted land owned by landlords for redistribution. Violent actions were carried out (dispersion of cattle, intimidation and others) to push landlords to sell their lands to the Estate Commissioners, for the successive redistribution.

Sir Montagu Richard died in 1907 and his younger brother, Sir Benjamin Rupert Chapman, inherited the title of Baronet. He was mentally unstable, hence the widow of Sir Montagu Richard, Lady Caroline, looked after the family business and the estate.

In the same year, the Killua ranches were attacked and a cattle drive was carried out. Consequently, Lady Caroline accepted the provisions of the Irish Land Act and, in 1918, 1000 acres of the estate were subdivided among 48 tenants.

When Lady Caroline died in 1919, according to Sir Montagu Richard will, Killua Castle came into the possession of Major-General Richard Steele Rupert Fetherstonhaugh, who decided to sell the property to a Colonel William Hackett from County Laois, after centuries of tenure by the Chapman family. This happened in 1921.

The new owner converted the grounds around the house into a golf course, which ran until 1938 and, after he died in 1942, the property passed to his widow, who put the lands and the castle on sale. As Mrs Hackett was not able to find a single buyer, the castle was piece by piece dismantelled and its items and fittings were individually sold in 1944; not long after, the castle's roof was removed and its lead sold.

In 1967 the property was transferred to the Irish Land Commission and later divided into units separately sold to privates. The Keane family from Mayo obtained the largest part, including what was left of the castle, the obelisk and the lake.

Lawrence of Arabia

Another interesting story enriches the charming plot of events and the interweaving of lives evolving and interacting at Killua Castle but we need to flashback to Sir Montagu Lowther and Sir Benjamin James (the 3rd and 4th Baronets) to find out more. The reader might remember there was a third brother William, born at Killua in 1811. William got married in 1841 and moved to Delvin, where he had 4 children, before dying in 1889. The eldest son, William Eden, died soon and the second son, Thomas Robert Tighe, married in 1873 Edith Sarah Hamilton Rochfort-Boyd, from whom he had 4 daughters. Some time after, an affair began between Thomas Robert and the nursemaid, Sarah Junner or Lawrence. After less than 3 years, Sarah resigned because she was secretly pregnant by Thomas, who found an accomodation for her in Dublin. In 1885, Montague Robert was born, from that relationship.

Either by accident or due to the work of a detective recruited by Edith, the truth finally came out and Thomas was forced to leave his wife and the house they were sharing. Thomas and Sarah then first moved to Wales with Montague Robert and, in 1888, their second son Thomas Edward Lawrence was born. Three more sons followed. The family finally settled in Oxford, where they were living under the name Lawrence, keeping their origins hidden. Thomas Chapman, now known as Tommy Lawrence, inherited the title of 7th Baronet in 1914 and, upon his death in 1919, in the absence of legitimate male heirs, the title became extinct.

We know many events that characterized the adventurous and restless life of Thomas Edward, British army officer and archaeologist, involved in the Arab Revolt and Sinai and Palestine campaign against the Ottoman Empire in the First World War, brilliantly captured in the movie “Lawrence of Arabia” by David Lean. We don’t exactly know how Thomas Edward knew the true story of his family (perhaps, he found it out in a letter written by his father). We know that Lawrence wished to acquire Killua at some stage in his life and there are even suspects that he visited Killua. Lawrence died aged 46 after a motorbike accident.

Resurrection of the castle

If our visitors had the interest (and patience) to read this story up until now, we are sure that they would be left pervaded by a bitter feeling, learning how the prosperous estate around Killua rose to its prime and, out of sadden, under the unbearable strength of uncontrollable fortunes, it turned into a roofless silent shell, sharing his glorious experience with aggressive weeds and ivy ramping over its walls and with its rooms occupied by gloomy crows and only visited by careless cattle.

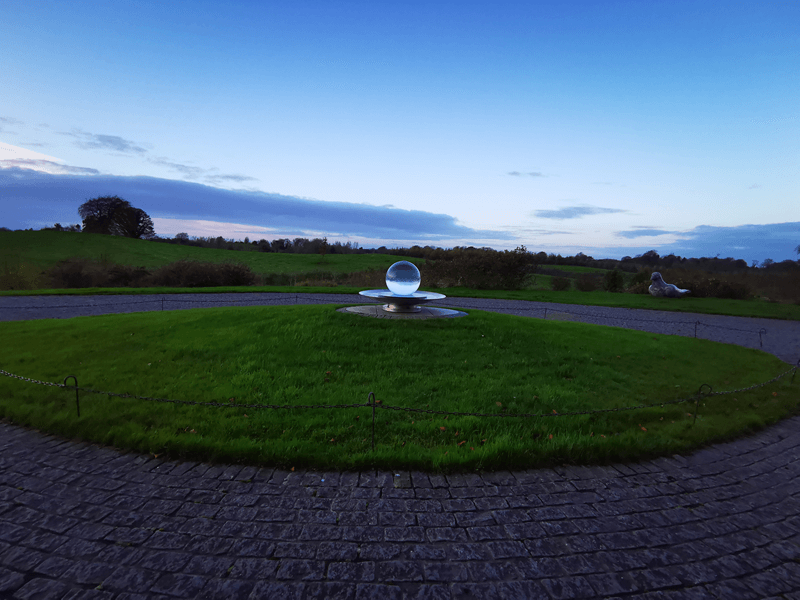

This could not be the end, it would have been unfair. So we have a surprise. In 1999, the Keane family sold the property to the current landlord, Allen Sanginés-Krause, a fine gentleman with a deep passion for medieval art, who stabilized and reconstructed the castle, that he defines an eclectic residence [6]. The splendour of that glorious past is now restored at Killua, meeting the present needs of sustainability, while preserving the environment and the richness of a unique territory.

References

- [1] Andrew Hugher, “Killua - A History”, edited by Luna Ventures Limited.

- [2] Killua Castle

- [3] Westmeath Examiner, History of Killua Castle the subject of new book

- [4] Daily Scribbling, Killua Castle – Potatoes, TE Lawrence, and rescue from decay

- [5] The History of Parliament, CHAPMAN, Montagu Lowther (1808-1852), of Killua Castle, co. Westmeath

- [6] Castles and Families, Killua Castle

Other useful links

- The Irish Times, From Mexico to challenge of a castle in Westmeath

- NBHS, Killua Castle, KILLUA, Clonmellon, WESTMEATH

- NBHS, Killua Castle, KILLUA, Clonmellon, WESTMEATH

- Familypedia, Killua Castle

- Wikipedia, Killua Castle

- Top One Hundred Attractions, Killua Castle

- Wikipedia, Desmond Rebellions

- Wikipedia, Siege of Smerwick

- Wikipedia, Walter Raleigh

- Wikipedia, Irish Confederate Wars

- Wikipedia, Constitution of 1782

- Wikipedia, Henry Grattan

- Wikipedia, Irish Rebellion of 1798

- Wikipedia, Daniel O'Connell

- Wikipedia, Irish National Land League

- Wikipedia, Irish Land Commission

- Wikipedia, Land Acts (Ireland)

- Wikipedia, Hugh de Lacy, Lord of Meath

- Wikipedia, T. E. Lawrence

- Wikipedia, Lawrence of Arabia (film)

- Geneanet, Thomas Robert Tighe CHAPMAN

- Wikipedia, Chapman baronets